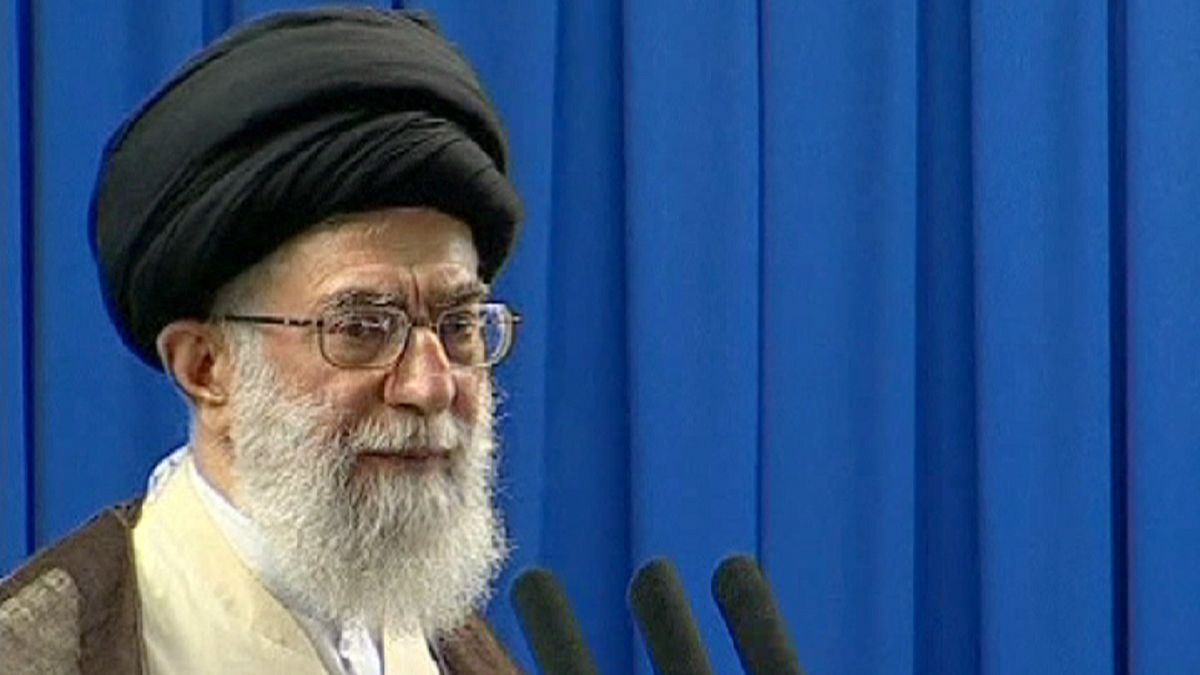

The West knows him as “the Ayatollah”, although the veracity of the religious title is debatable. So is the way the ruling system has tailored it. Who is this so-called ayatollah? Here, we discuss his exalted position with Dr Kazem Alamdari, a sociology professor at California State University. But first, let’s look at a few facts.

Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Hosseini Khamenei, stands above its head of state, its judiciary and the legislature – the three foremost branches of power. A 74-year-old cleric, therefore, is the top figure… in a country that plays such an important role in the Middle East. Commander of the armed forces, he appoints all its military chiefs. The authority to declare war or call a referendum rests with him.

Khamenei succeeded Khomeini, who led the 1979 Revolution. His duties have included appointing the heads of the Judiciary and the state media apparatus, and also half the members of the Guardian Council – those overseeing Islamic jurisprudence. This Council checks new laws passed by the parliament, and vets presidential and parliamentary candidates.

Khamenei doesn’t have to charismatic, and he isn’t seen that way by the many protesters who have destroyed the top political figure’s portrait in the streets of the capital, shouting: “Down with the Dictator!” – at the risk (women included) of being clubbed over the head by security forces wielding batons.

Iran’s leader branded the widespread protests over the result of the previous, 2009, presidential elections as “sedition”. Two of the candidates of those polls, Mirhossein Moussavi and Mehdi Karoubi, are still under house arrest.

The unwritten punishment for criticizing the leader of the Islamic Republic can include anything from temporary detention to being killed – ‘physical removal’ is a term in vogue now.

In 1997, a German court held Khamenei and then-President Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani responsible for the assassination in 1992 of three opposition member in Berlin.

Khamenei describes himself as a revolutionary. He has said he is not a diplomat, but many signs point to his office as the place where all matters of supreme importance are decided, such as policy on relations with the United States and Iran’s nuclear activities.

Ali Kheradpir, euronews: “Professor Alamdari, is there any similarity in any other country to Mr Khamenei’s political and religious position as enshrined in the Iranian Constitution?”

Kazem Alamdari: “The Absolute Supreme Leader has unlimited authority. In the world today, there are more than a few dictators and law-breakers but I do not see any case like Iran’s, in which the constitution bestows dictatorship rights on a leader. This dictatorship is the result of the merger of the two power institutions of religion and government, and of the leadership position being accorded for the man’s lifetime. These two factors, along with Mr Khamenei’s monopolising spirit, have created a phenomenon which is unique in the world.”

euronews: “How do you see the process by which the Iranian leader attained power? In what way does his position balance power with legitimacy?”

Alamdari: “This leader’s coming to power was the result of a big conspiracy against the legal heir to Ayatollah Khomeini, Ayatollah Montazeri, who was also a member of the House of Experts, from among whose number a successor is elected. After the death of Khomeini, Rafsanjani claimed that Khomeini had named Khamenei to become leader. This is in spite of the fact that no such thing was mentioned in Khomeini’s 30-page will. After Khomeini’s death, Khamenei and Rafsanjani marginalised Ayatollah Khomeini’s son, Ahmad, and they shared power between them. Two years later, Ahmad died in suspicious circumstances. After that, Khamenei and Rafsanjani’s views began to diverge. Rafsanjani looks ahead while Khamenei looks to the past; he is anti-Western and against modernity. With his monopolising attitude, and aided by the military and hardline conservatives, Khamenei managed to marginalise Rafsanjani, as well.”

euronews: “Looking at what happened with the reformist protests surrounding the last presidential elections, can we say that the leader interferes with the election process?”

Alamdari: “Yes. The leader interferes with the elections. The third year into Ahmadinejad’s term, the leader said in a speech that Ahmadinejad should not assume that his presidency had only one year left to run, and that he should prepare himself for the five years after that. Therefore, in the last presidential elections, Khamenei used his influence to direct the process in favour of Ahmadinejad and against Mousavi. To Khamenei, a president’s independent stance can be interpreted as a dual authority within the system and a threat against his own absolute power. Even in this period, he acted against Khatami and Rafsanjani and prevented their candidacies.”

euronews: “In your view, what is the most important challenge the leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran is facing?”

Alamdari: “The women’s movement for freedom, democracy and equality; the very bad economic conditions, the international sanctions and global isolation – these are the main challenges Khamenei faces.”