The summit:

As youth unemployment hits 50% in some areas, leaders at the European Union summit in Brussels announced a series of measures and a pledge of €6bn to tackle the problem. Several years of austerity policies and spending cuts have sent youth unemployment rates rocketing. Nearly a quarter of people aged 18 to 25 in the EU have no job, and that rate grows to 50% in Spain and Greece.

In May this year during a speech in Madrid, László Andor, the European Commissioner responsible for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, said: “We simply cannot sit idly when 7.5 million Europeans under 25 years of age are neither in employment nor in education or training. We need their talents, skills and experience, their capacity to invent, innovate and create. These are all driving forces for our collective prosperity.”

Herman Van Rompuy, head of the European Council, added in a press release on Monday: “As a matter of priority we should speed up the Youth Employment Initiative, set up Youth Guarantee schemes, mobilise all available resources in support of youth employment and increase youth mobility, all of this with the full involvement of social partners.”

Unemployment:

The graph below shows the rates of unemployment and youth unemployment (under 25s) in various European countries.

The averages are shown for the Euro area (EA17), which consists of: Belgium, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Austria, Portugal, Slovenia, Slovakia and Finland, and also for EU27 which refers to the 27 member states of the European Union.

The measures:

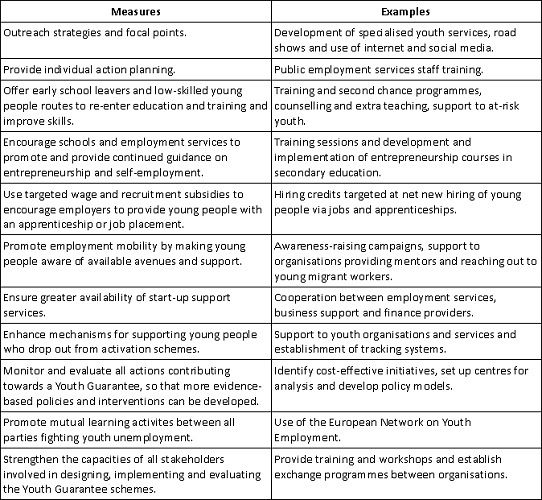

The EU Commission adopted the Youth Guarantee Recommendation in April this year, which aims to offer all young people a job, an apprenticeship, a traineeship, or continued education within four months of becoming unemployed or leaving formal education.

In addition, the European Investment Bank will borrow on the markets to increase lending to small businesses, in an attempt to bypass the credit crunch and encourage the hiring of school-leavers.

The estimated cost for establishing the scheme in the eurozone is €21 billion. However, the Commission notes that this should be compared with the costs of unemployment and lost productivity, estimated at an annual loss of €153 billion for the EU. Futhermore, being unemployed at a young age can have long-term negative effects such as exclusion, poverty and health problems.

The impact:

Whilst the figures sound impressive, few in Brussels seem convinced they will have a real impact. The President of the European Parliament, Martin Schulz, described the amount as “a drop in the ocean”. German Chancellor Angela Merkel added, “the main thing here is about improving competitiveness. It is not about more and more pots of money”.

Economists have criticised the scheme as a public relations exercise and some believe the EU has been wrong to target only youth unemployment, rather than attempting to boost growth as a whole. It should be noted that many young people are leaving Europe in order to find work elsewhere; analysts fear this will lead to a “brain drain” as the best and brightest emigrate and leave southern Europe stagnating.

André Fourçans, an economics professor at ESSEC business school, believes that true structural measures against unemployment will come from national decisions and not European ones. One of his colleagues, Florin Aftalion, on the other hand, says that the only measure that will have a real effect on youth unemployment is the creation of a “youth minimum wage”.

Some analysts, like José Manuel Fernandes, the editor of the Portuguese newspaper Público, believe that high unemployment rates are here to stay. Fernandes says that although many modern economies are investing in heavy industry, this creates very few jobs, and can even lower the number of employees. It may be wise therefore to regard promises of ‘reindustrialisation’ with scepticism – while it may be beneficial for GDP, it will have little impact on the main issue of employment.

These problems also exist in other sectors where innovation has led to greater efficiency but fewer people, such as those linked to new technologies and biosciences. In these sectors, an increase in investment does not necessarily lead to an increase in jobs.

Fernandes notes that there are other factors working against the creation of jobs in Europe. There is a lack of innovation and the job market remains rigid. Most importantly, the population demographic is unbalanced and prevents young blood from entering the job market. Without economic growth of more than 2%, there is no net creation of jobs, meaning it is very difficult to reabsorb unemployment.

With an increase in life expectancy, many governments are pushing back the age of retirement. However, by remaining in the job market, older employees do not make space for the young, which translates into the record youth unemployment we are currently seeing. But because our economies cannot afford younger retirement, we are stuck. Fernandes believes we need innovative solutions, like the development of transition periods between work and retirement, characterised by part time jobs with lower salaries.