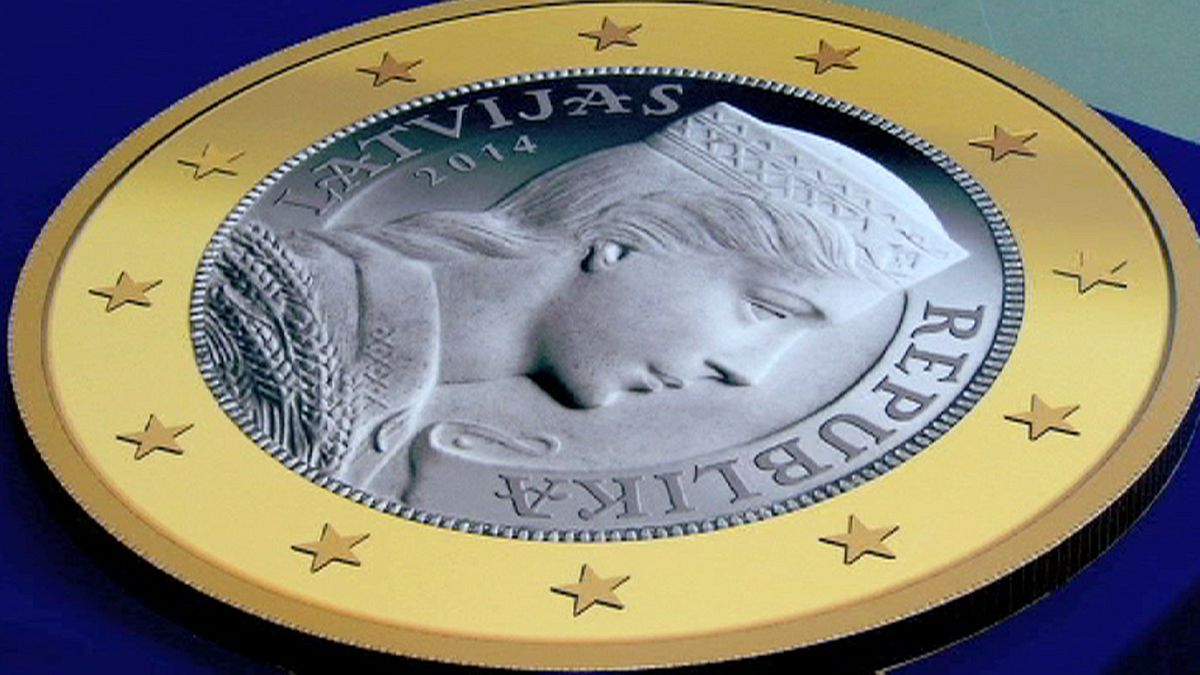

Latvia to adopt the euro

Numismatists all over the world will soon be able add a new coin to their collection: the Latvian-customized euro. Despite being a cherished symbol of the small Baltic state’s independence from the Soviet Union, with a unique history, Latvia’s currency, the lat, will stop being distributed as of 1 January 2014. The country will become the 18th member of the European Union to use the euro.

Fanatics of statistics will be quick in pointing out that the Baltic state will be the poorest member of the single-currency area, with the highest inequality and a damaging demographic shift. Maybe, but with 5.2% growth in 2011, 5.6% in 2012, and 3.6% predicted for 2013, Latvia also has the fastest-growing economy in the European Union. Its will to join the eurozone, a bloc that has suffered excruciating pains since late 2009, was welcomed in the euro capitals as a token of trust in the future of the economic and monetary union.

Alongside its economic dynamism, the Council of the European Union, who gave the thumbs up to Latvia’s entry into the Eurozone on 9 July 2013, took stock of the Baltic state’s stamina and its fulfilment of the so-called stability-oriented economic criteria. Latvia suffered the world’s deepest recession when its economy shrank by 25% over two years, during the 2008-2009 global crisis. Yet, after the painful bursting of its credit bubble wages rose approximately 35% in 2007 – Latvians found the way to put their economy back on track, to refocus on exports and strengthen fiscal prudence. Exports of goods and services rose 15.2% in the fourth quarter of 2012 from a year earlier despite recession in Europe, which is the destination for 60% of Latvia’s shipments. 2012’s fiscal deficit was worth just 1.2% of gross domestic product and public debt 40.7% of GDP.

Critics of austerity argue that Latvia paid too high a price: its economy lost more than a fifth of its value and unemployment spiked to 17%. Although it fell to 11.80% in the third quarter of 2013, unemployment is a structural problem with two main roots: gross skills mismatch, stemming from an education system that produces too many social science graduates and too few, desperately-needed, computer programmers; and a sustained brain drain that started after Latvia’s accession to the European Union in 2004 and peaked after the 2008 financial crisis.

Closely intertwined with unemployment is Latvia’s demographic disaster. “Disaster” is not too strong a word when we consider that from a peak of 2.67 million in 1989, Latvia’s population sharply fell to 2.2 million in 2000 and 2 million in 2011, according to census figures. It is a plunge of 13.0% in little more than a decade. An ageing population, a low fertility rate and rising emigration are to blame. Worse still, according to a study of Latvia’s economy ministry, if nothing is done to tackle the exodus of young Latvians – for whom Britain and Ireland are their two main destinations – the population could drop to 1.6 million by 2030. The punch line of a running joke in Latvia says that in 2030, the last Latvian leaving the country could switch off the lights at Riga airport.

And then, there are the Latvian banks, a real source of concern in Brussels and Frankfurt. About half of all deposits represent non-resident deposits, much of them from Russia, Belarus, Uzbekistan, and other countries of the former Soviet Union. Laws that allow foreigners who buy expensive Latvian real estate to apply for resident visas, giving them the right to travel throughout the European Union, have drawn hundreds of investors from Russia and beyond.

Advising it to closely monitor its financial flows, the European Commission insists that Latvia beef up funding and staffing for law enforcement and the judiciary to tackle “complex economic, financial, money laundering and tax evasion crimes.”

On the top of all this, the Baltic state adds to its euro-launch challenge the political complications of appointing a new Prime Minister and holding parliamentary elections in October 2014. The current acting head of the government, former Prime Minister Valdis Dombrovskis, resigned in November 2013 after a fatal supermarket collapse in Riga.

But while all’s not quite rosy in Riga, and Latvians are strongly sceptical about the benefits of adopting the euro, the Latvian folk-maid’s cherished profile, historical symbol of virtue and righteousness so dear to their hearts, will move from the reverse of the 5-lats coin to the reverse of the 1-euro and 2-euro ones. Numismatists all over the world won’t be disappointed!