China- Japan relations

Expect your neck to twist and turn in 2014, while watching the Sino-Japanese tensions in the East China Sea spiralling upwards. Chances are high that Beijing and Tokyo will continue what seems to be the beginning of a cold war over the disputed seven square kilometres of the Diaoyu or Senkaku Islands, as they are respectively called by the Chinese and Japanese. These five uninhabited islets and three barren rocks situated in the East China Sea are at the heart of a territorial feud between the two most powerful Asian countries.

What is it about these tiny islets – the largest of which is home to just a few hundred feral goats, and an endangered species of mole – that makes them so special to both Japan and China?

Firstly, historical resentments and nationalist politics figure heavily in this territorial dispute. The Chinese claim the discovery and control of the islands from the 14th century while Japan controlled them from 1895 until its surrender at the end of World War II. The United States administered the islands from a 1945 to 1972, when the islands reverted to Japanese control, under the Okinawa Reversion Agreement between the United States and Japan. The People’s Republic of China disputed the proposed US handover of authority to Japan in 1971 and has asserted its claims to the islands since that time. Taiwan (Republic of China) also claims the Senkaku Islands.

There are observers who consider that the relationship between China and Japan encompasses Asia’s most dangerous case of historical obsession. Some analysts also say that, due to the link with atrocities committed during the Japanese invasion of China, in the second Sino-Japanese War, sentiments over the status of the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands run deeper in the Chinese psyche than any other territorial dispute in modern Chinese history.

Secondly, the small territory of the islets is close to key shipping lanes and rich fishing grounds.

But there’s another, much potent ingredient, that fuels this tensed face-off: energy. A United Nations-led geological survey in 1969 has found that large oil and natural gas reserves are at stake under the East China Sea, lying around the Senkakus and beyond. So the idea that there are vast resources just off the Japanese and Chinese coasts is a tremendous motivation for the intensity of their territorial dispute, as point out analyst of the Council on Foreign Relations, a think-tank based in Washington, D.C.

China is the world’s largest energy consumer, and its consumption is growing 6% each year, fast outstripping supply. As advances in deep-water drilling technology have put offshore oil and gas resources within reach for the first time, the result is, as the independent NGO International Crisis Group frames it, a race “to assert control over energy resources in disputed territories, before they are developed by a rival.”

Just how much oil and natural gas is at stake in the East China Sea is unclear. The territorial disputes have so far prevented any reliable survey. China estimates that one of the world’s largest natural gas deposits, containing some 250 trillion cubic feet, lies under the waters of the East China Sea. US energy analysts appreciate the “proven and probable” reserves there at only 1 to 2 trillion cubic feet – much less than the Gulf of Mexico, but still considerable.

Until recently, there was no way to exploit the riches of the East China Sea. The most promising petroleum prospect lies in water more than 2,500 meters deep, between the Chinese and Japanese continental shelves in the Okinawa Trough. And only in the past two decades has the oil industry developed the deepwater drilling technology.

Beyond the territorial-cum-energy contention and closely intertwined with it lie the fears triggered in the whole Eastern Asia by China’s more and more assertive positioning as a regional hegemony. In 2010, China started to take a more hardline approach towards Japan by increasing its aerial and law enforcement presence in disputed waters, to demonstrate its sovereignty. For Japan, 2010 was altogether an annus horribilis, known there as the “China shock”. That’s when China eclipsed Japan to become the world’s second-largest economy. This triggered an upsurge in Japanese nationalist sentiment, culminating in campaigns to name, and even to purchase, the disputed islands.

Chinese hardliners see these moves as Japan’s willingness to act as a proxy of the US in its efforts to contain China’s rise and expand US presence and influence in the Asia-Pacific region. In Japan, what is perceived as China’s determination to restructure the regional landscape is fuelling nationalist anxiety about Japan’s ability to defend its territory against a Chinese expansion.

No wonder, then, that on 17 December 2013, in Japan’s newly drafted National Security Strategy – the first comprehensive effort to articulate the ends and means for the country’s long-term security – while North Korea remains a serious challenge, the cabinet of the hawkish Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has clearly identified China and its maritime activities as Japan’s primary security concern. Named a “proactive strategy for maintaining peace,” the plan comes with a 5% increase in Japan’s military spending over the next five years.

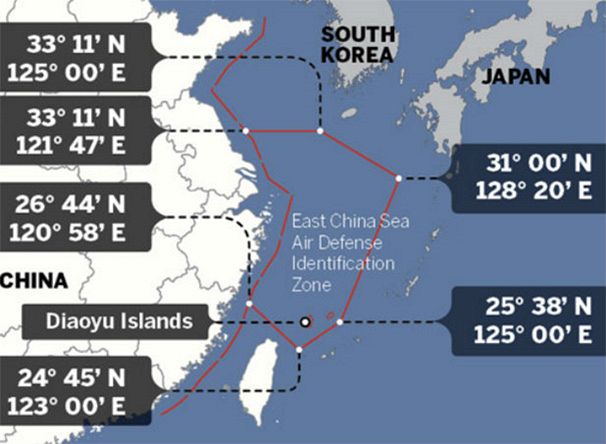

China’s rise and “intensified activities” in and around Japan stand out in this new strategy. The Senkaku islands dispute with China has prompted considerable Japanese attention to its south-western defences. Whereas past defence statements have tended to focus on China’s growing military capabilities, this new strategy clearly focuses on Chinese behaviour. It identifies Chinese incursions into Japan’s territorial seas and airspace around the islands and Beijing’s announcement of the unilateral expanding of its air patrol zone – the so-called Air Defense Identification Zone – to include islands and rocks where sovereignty is disputed, as evidence of “attempts to change the status quo by coercion.”

As for the region as a whole, one cannot but wish that diplomacy, that “art of restraining power”, as former US State Secretary Henry Kissinger called it, finds its place in the fraught Sino-Japanese relations, before they grow to become a zero-sum game.