Saudi Arabia and Lebanon's installations at the Venice Biennale seek to redress the balance by questioning masculine views and Western myths surrounding the portrayal of women in Middle Eastern societies.

In the desert-hued pavilion of Saudi Arabia at the Venice Biennale, a rising harmonised humming fills the space.

These are the voices of some 1,000 Saudi women that artist Manal AlDowayan has “brought with her” to the international exhibition.

With her all-female team of curators, AlDowayan’s installation aims to be a rebuttal of the international media’s preconceptions of women in Saudi Arabia and an amplification of their own voices instead.

In Lebanon’s pavilion, artist Mounira AI Solh challenges the male gaze and the way it has shaped the ancient myth of Europa.

Like AlDowayan, she returns the narrative power to the woman.

Venice Biennale: Saudi pavilion silences international stereotypes

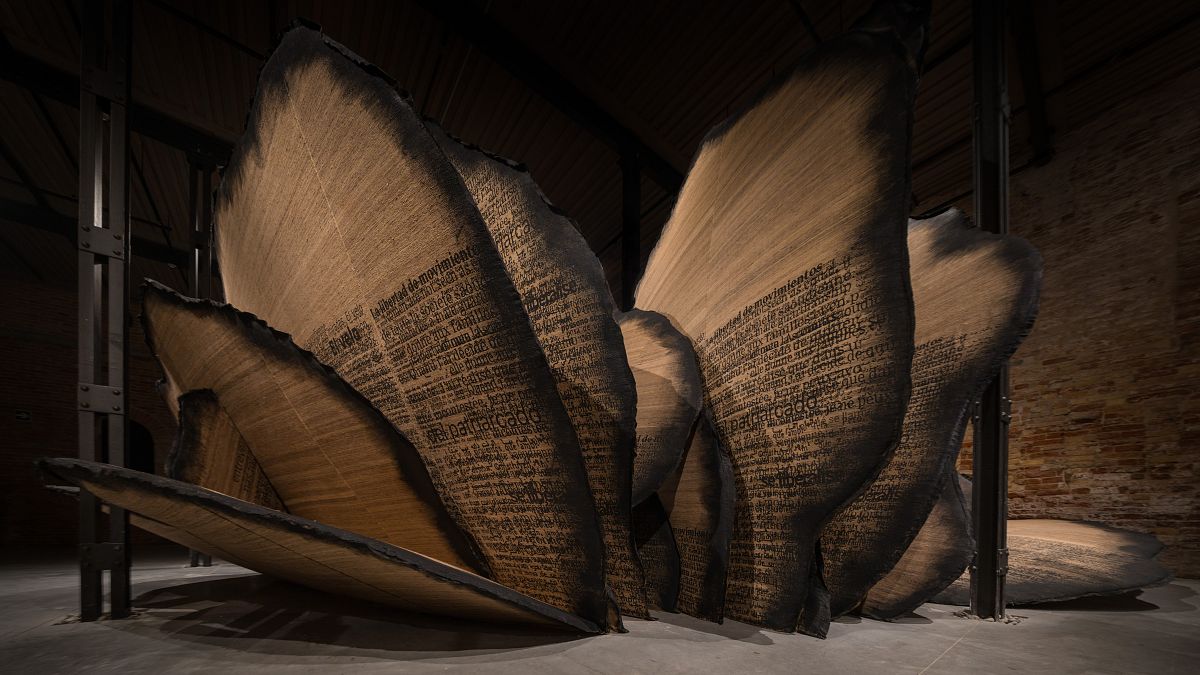

The Saudi pavilion in the Arsenale is filled with giant, roughly circular silk panels suspended vertically from the ceiling or rising up from the floor.

They recall the desert rose, a crystal formation that appears in the dunes near where AlDowayan lives.

“In Western literature, women always seem to be compared to a delicate English rose,” she tells me. “But the women I know are not like that at all.”

Forming under duress by intense rainfall followed by extreme heat, the desert rose represents the strength and power of Saudi women for AlDowayan.

Grouped into arrangements, the beige silk panels nearest the front and back entrances are heavily inked with newspaper text.

The writing overlaps but some emboldened phrases remain legible: ‘repressed’, ‘an enigma’, ‘the Dark Ages’.

“The European press is obsessed that they can’t see us under the veil,” explains AlDowayan. “So they decided to choose their narrative for the Arab world.”

Most of the other typed phases are obscured. For AlDowayan, this represents the “cacophony of media that constantly surrounds the Saudi women” that she has disempowered.

1,000 women’s voices sing in the Saudi pavilion

The crystal formations in the centre of the room are instead decorated with decipherable lines of poetry and distinct drawings.

There are images of raised fists and a scale with a man and woman balanced equally, and dozens of uplifting phrases in English and Arabic.

These were produced during three separate workshops in Saudi Arabia with over 1,000 women participants of all ages.

They were invited to read the media articles about Saudi women and react.

“I feel so proud and grateful for their support,” AlDowayan says. “It was a sense of solidarity that I needed to repay so I brought them all with me symbolically to Venice and placed them at the heart of my work.”

As you wander around, the swelling noise of humming begins over loudspeakers. This recreates the ‘singing’ that emanates from sand dunes when they move.

“The sound is made when tiny grains rub together,” explains curator Shadin AlBulaihed. “It shows that small voices can make a big sound.”

“We are entering a new stage in Saudi Arabia where women are given many more opportunities and rights,” adds AlDowayan. “We need to redefine how our bodies and voices exist in the public sphere.”

‘We need to take back our stories’: Lebanon pavilion confronts the male gaze

In Lebanon’s pavilion, Mounira AI Solh is busting a millennia-old myth, going right back to the country’s origins and its Phoenician ancestors.

In A Dance with Her Myth, Al Solh examines the story of the Phoenician princess Europa who is seduced and abducted by Zeus, disguised as a white bull.

Over the centuries, particularly in Western painting, the representations of the myth have evolved from abduction to consent - always dictated by the male gaze.

AI Solh, instead, chooses to reinterpret the myth with gender equality. She upsets the balance of power between the dominating god and the dominated princess.

Princess Europa cooperates with Zeus and manipulates him; “it is she who holds him and carries him away by walking on water, she who tosses him around with her feet as if he were a kicking ball.”

In her quest, the artist pushes the deconstruction of gender stereotypes to the extreme, by reversing the roles and the sexes - including Hercules’ dog who becomes female.

A Dance with Her Myth is set up around a boat, inviting visitors on a symbolic journey of emancipation and gender equality. Its unfinished structure indicates that the journey is not fully completed.

On the boat’s sail, a 12-minute film is projected with scenes of the goddess spinning an urn containing a bull’s head. “I looked for a magnificent white bull … but all I found was a goat,” reads a line of poetry.

“I want to show that we, as women, do not want to play the role as victims,” AI Solh said in an interview with pavilion curator Nada Ghandour. “We need to take back our stories, colour them, change them, reverse them, turn them around, in order to reappropriate them.”