Scientists agree that human-caused climate change is by far the biggest cause - but what else is at play?

This summer’s record-shattering heat has been fuelled by global warming and El Niño. But scientists are wondering if there are other factors at work.

The European climate agency Copernicus reported that July was one-third of a degree Celsius hotter than the old record. This bump in heat is so recent and so big - especially in the oceans - that scientists are split on what's behind it.

Scientists agree that by far the biggest cause of the recent extreme warming is climate change from the burning of coal, oil and natural gas that has triggered a long upward trend in temperatures.

A natural El Niño, a temporary warming of parts of the Pacific that changes weather worldwide, adds a smaller boost. But some researchers say another factor must be present.

“What we are seeing is more than just El Niño on top of climate change,” says Copernicus Director Carlo Buontempo.

From shipping to volcanoes, here are some ideas under investigation.

Is cleaner air from shipping regulations unmasking global warming?

Florida State University climate scientist Michael Diamond says shipping is "probably the prime suspect".

Maritime shipping has for decades used dirty fuel that gives off particles that reflect sunlight in a process that actually cools the climate and masks some of global warming.

In 2020, international shipping rules took effect that cut as much as 80 per cent of those cooling particles. This was a “kind of shock to the system,” says atmospheric scientist Tianle Yuan of NASA and the University of Maryland Baltimore County.

The sulfur pollution used to interact with low clouds, making them brighter and more reflective, but that’s not happening as much now, Yuan says. He tracked changes in clouds that were associated with shipping routes in the North Atlantic and North Pacific, both hot spots this summer.

In those spots, and to a lesser extent globally, Yuan’s studies show a possible warming from the loss of sulfur pollution. And the trend is in places where it really can’t be explained as easily by El Niño, he says.

“There was a cooling effect that was persistent year after year, and suddenly you remove that," Yuan says.

Diamond calculates a warming of about 0.1 degrees Celsius by midcentury from shipping regulations. The level of warming could be five to 10 times stronger in high shipping areas such as the North Atlantic.

A separate analysis by climate scientists Zeke Hausfather of Berkeley Earth and Piers Forster of the University of Leeds projected half of Diamond's estimate.

Is a volcanic eruption fuelling global warming?

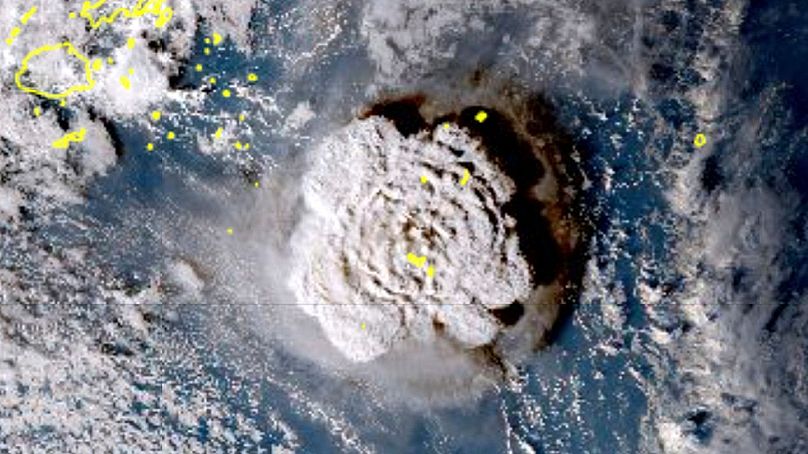

In January 2022, the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai undersea volcano in the South Pacific blew. It sent more than 150 million tonnes of water - a heat-trapping greenhouse gas as vapour - into the atmosphere, according to University of Colorado climate researcher Margot Clyne, who coordinates international computer simulations for climate impacts of the eruption.

The volcano also blasted 500,000 tonnes of sulfur dioxide into the upper atmosphere.

The amount of water "is so absolutely crazy, absolutely ginormous,” says Holger Vomel, a stratospheric water vapour scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, who published a study on the potential climate effects of the eruption.

Volmer says the water vapour went too high in the atmosphere to have a noticeable effect yet, but that effects could emerge later.

A couple of studies use computer models to show a warming effect from all that water vapour. One study, which has not yet undergone the scientific gold standard of peer review, reported this week that the warming could range from as much as 1.5C of added warming in some places to 1C of cooling elsewhere.

But NASA atmospheric scientist Paul Newman and former NASA atmospheric scientist Mark Schoeberl says those climate models are missing a key ingredient: the cooling effect of the sulfur.

Normally huge volcanic eruptions, like 1991’s Mount Pinatubo, can cool Earth temporarily with sulfur and other particles reflecting sunlight. However, Hunga Tonga spouted an unusually high amount of water and low amount of cooling sulfur.

The studies that showed warming from Hunga Tonga didn’t incorporate sulfur cooling, which is hard to do, Schoeberl and Newman say. Schoeberl, now chief scientist at Science and Technology Corporation of Maryland, published a study that calculated a slight overall cooling - 0.04 degrees Celsius.

Just because different computer simulations conflict with each other "that doesn’t mean science is wrong,” University of Colorado's Clyne says. “It just means that we haven’t reached a consensus yet. We’re still just figuring it out.”

African dust and stars are lesser suspects

Lesser suspects in the search include a dearth of African dust, which cools like sulfur pollution, as well as changes in the jet stream and a slowdown in ocean currents.

Some nonscientists have looked at recent solar storms and increased sunspot activity in the sun's 11-year cycle and speculated that Earth's nearest star may be a culprit. For decades, scientists have tracked sunspots and solar storms, and they don’t match warming temperatures, Berkeley Earth chief scientist Robert Rohde says.

Solar storms were stronger 20 and 30 years ago, but there is more warming now, he says.

Human-caused climate change boosted by El Niño remains primary cause

Still, other scientists said there’s no need to look so hard. They say human-caused climate change, with an extra boost from El Niño, is enough to explain recent temperatures.

University of Pennsylvania climate scientist Michael Mann estimates that about five-sixths of the recent warming is from human burning of fossil fuels, with about one-sixth due to a strong El Niño.

The fact that the world is coming out of a three-year La Nina, which suppressed global temperatures a bit, and going into a strong El Niño, which adds to them, makes the effect bigger, he says.

“Climate change and El Niño can explain it all,” Imperial College of London climate scientist Friederike Otto says. “That doesn’t mean other factors didn’t play a role. But we should definitely expect to see this again without the other factors being present.”