Researchers studied how the hippocampus supports memory functions.

Despite extensive research, there are still many aspects of how the brain functions that remain unknown.

A team of researchers from Cornell University have now discovered how the hippocampus supports two memory functions.

They found in a study on rats that one function involved remembering associations such as between time and place, while the second was to predict or plan future actions based on past experiences.

“We uncovered that two different neural codes support these very important aspects of memory and cognition, and can be dissociated, as we did experimentally,” said Antonio Fernandez-Ruiz, assistant professor of neurobiology, in a statement on Cornell's website.

This could help for future treatment of memory problems in people struggling with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Use of ‘optogenetics’

For the study published in Science, the scientists focused on the hippocampus, an area of the brain that plays a major role in memory function.

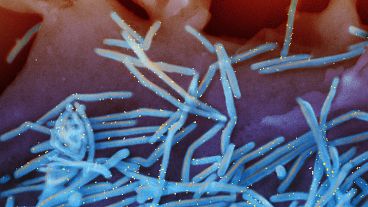

They used optogenetics, a method using light to turn cells on or off, to control the activity of neurons in a rat’s brain.

Using a virus injected into a rat’s brain, they could perturb specific neurons to disrupt a certain region in the hippocampus, such as that used to learn a new itinerary.

The sequence of steps along such an itinerary is "encoded in the brain as a sequence of cells firing," according to Fernandez-Ruiz.

“The way we will remember this in the future is that when we are sleeping, the same sequence of activity is replayed, so the same neurons that encode [the path] will fire in the same order," he added.

Researchers observed that due to the scrambling, the neurons failed to solidify the memory during sleep. As a consequence, the rat was unable to remember the pathway though it was able to remember the departure and arrival point.

"The associative aspects of memory were maintained, but the predictive part of it was lost," explained the team.

In one of their experiments, the rats had to explore a maze and were rewarded when they managed to find a new path. The rats could not remember how to get the reward.

However, when the reward was associated with a precise location, the associative memory worked even when the predictive function did not.

Hope for the future?

Memory loss is a key symptom of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. One of the physical symptoms of Alzheimer’s is the reduction of the hippocampus’ size which can occur years before the first symptoms of disease.

The researchers said that this study can contribute to understanding "how memory associations develop into predictive representations of the world and helps reconcile previously disparate views on hippocampal function."

Fernandez-Ruiz said: "By looking at which type of memory deficits occur in a patient, we can try to infer what type of underlying neuronal mechanism has been compromised, which will help us develop more targeted interventions."