A new blood test from researchers at Oxford University could identify people at risk for Parkinson’s disease years before symptoms manifest.

Researchers at Oxford University have unveiled a blood test that could pinpoint with 90 per cent accuracy whether a person is at risk of developing Parkinson's disease.

The condition is one of the most common neurodegenerative disorders. In Europe, it’s estimated that between 1 and 2 per cent of people over the age of 65 are living with the disease.

The physical symptoms of Parkinson’s include tremors, impaired or slower movements, and more rigid muscles. There is also a psychological impact, with sufferers of the disease also experiencing depression, anxiety and dementia. These symptoms worsen over time.

Diagnosing Parkinson's can be challenging due to how common a lot of the symptoms are. Chances of delaying the disease’s progression diminish the longer a diagnosis is delayed, according to Parkinson’s Europe.

However, the blood test developed by the University of Oxford team could help to speed up the process.

“A screening test that could be implemented at scale to identify the disease process early is imperative for the eventual instigation of targeted therapies as is currently done with screening programmes for common types of cancer,” George Tofaris, professor at the Department of Clinical Neurosciences at the University of Oxford, said in a statement.

What is alpha-synuclein?

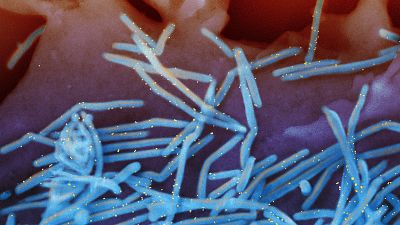

The team used an improved version of an antibody test to measure levels of alpha-synuclein - a small protein that is associated with Parkinson’s - in the blood.

Parkinson's disease begins to take hold over a decade before the manifestation of noticeable symptoms in patients, as their brain cells struggle to manage the impact of alpha-synuclein.

These proteins build up and end up in abnormal clusters which harm susceptible nerve cells, giving rise to the well-known movement disorder and frequently leading to dementia.

At the point of diagnosis, a substantial number of these susceptible nerve cells have already perished, and alpha-synuclein clumps have developed in numerous regions of the brain.

The Oxford team focused on a specific type of extracellular vesicles - tiny particles released by all cell types - which travel through bodily fluids, including blood, facilitating the communication of molecular signals between cells.

This sophisticated test isolates extracellular vesicles originating specifically from nerve cells in the blood - less than 10 per cent of all circulating vesicles - and quantifies the amount of alpha-synuclein present in them.

Vesicles carry essential messages, proteins, and genetic material from one cell to another. They basically form a sophisticated cell-to-cell messaging system but on a molecular level.

They play a vital role in maintaining the balance and coordination of bodily functions.

The team at Oxford University now believe that nerve cells may protect themselves by packaging the excess protein in extracellular vesicles, which are then released into the blood.

90% accuracy

In a study carried out by the Oxford team on 365 people, individuals with the highest risk of developing Parkinson's (more than 80 per cent probability based on research criteria) showed a two-fold increase in alpha-synuclein levels in neuronal extracellular vesicles.

The test accurately differentiated them from those with low-risk or healthy controls, with a 90 per cent probability of distinguishing someone with high risk from a healthy control.

In a subgroup of 40 people who later developed Parkinson's and related dementia, the blood test was positive in more than 80 per cent of cases up to seven years before the official diagnosis.