The exhibition, With my eyes, has sight and perception at its heart and controversially transforms the Vatican pavilion from a women's jail into a gallery.

As well as showcasing spectacular and startling contemporary art, the Venice Biennale is an opportunity to gain access to some of its rarely opened buildings.

This year, the Vatican’s pavilion can claim the accolade of most unusual location. If you’ve already visited the canal city, it's still highly unlikely you’ve entered this building - the Holy See’s exhibition is housed in Venice’s women’s prison.

In a sense, the Vatican’s pavilion is a piece of months-long performance art in which the visitor is a participant. The experience is about far more than the art on the walls - it’s about the interaction with the inmates and the glimpse into their world behind walls. As the organisers write, “the object of discussion will be art, poetry, humanity, and caring.”

The show is titled Con i miei occhi (With my eyes), taken from a fragment of poetry inspired by an ancient sacred text and an Elizabethan poem. “I do not love thee with mine eyes” (Shakespeare, Sonnet 141) echoes a line from the Book of Job: “now mine eye seeth thee”.

“A cross-fade, gradually becoming an action where seeing is synonymous with touching, with the gaze, embracing with the eye, bringing sight and perception into a dialogue with each other,” the rather obscure pavilion description reads.

The phrase becomes more literal on arrival at the prison, a 13th-century building on the Giudecca that began as a convent and then became a reformatory for unwed mothers and sex workers. Sight and perception are at the heart of the experience - for a start you have to hand over your phone.

You also view the exhibition through the dialogue and interaction with the female prisoners who act as guides dressed in the dark blue and white uniform designed and sewn in the in-house workshops. They explain the artworks, but also drop in comments about the penitentiary spaces and services.

From feet to films: The artworks are on show at the Vatican Pavilion

The exhibition is crowded with stellar works selected by curators Chiara Parisi and Bruno Racine. Perhaps the most dramatic is Italian-born artist Maurizio Cattelan’s dirty feet. The giant photograph graces the facade of the prison chapel, referencing Andrea Mantegna’s painting Lamentation Over the Dead Christ.

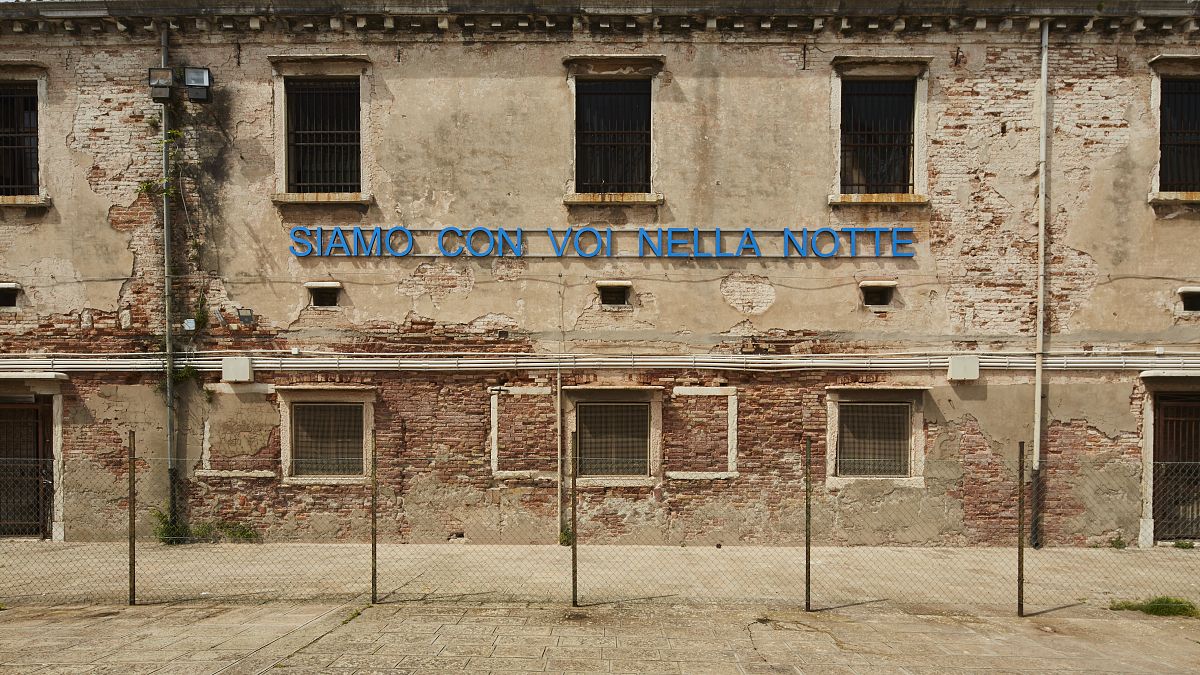

On a wall in a courtyard, a work by Palermo-based collective Claire Fontaine features large neon text reading “Siamo con voi nella notte” (We are with you in the night) - a message of solidarity to the inmates from the outside world.

There are also the graphic sloganed posters of Corita Kent - who spent part of her life as a nun - and glazed volcanic slabs painted by the artist Simone Fattal with excerpts of poetry written by the inmates. The prisoners also contributed to a film by the artist Marco Perego where they act alongside Zoë Saldaña, Perego’s wife. It is a deeply moving portrayal of female friendship and life inside.

Vatican pavilion sparks concern over prisoner collaborations

Allowing outsiders a glimpse of a life normally away from the public eye has not been without controversy. Two Italian curators who have previously exhibited at the penitentiary have raised concerns that the pavilion encourages voyeurism. They also cite concerns over uncompensated labour for the prisoners conducting tours and collaborating in artworks.

While sight is at the heart of the exhibition, it inevitably means that the visitor also dwells on its opposite - what is hidden. Not only do you come away with no photos, but you are not allowed to ask the imprisoned women personal questions nor can you know their surnames. Is this for the inmates’ privacy or to control what they communicate to visitors?

Come the end of November and the closure of the Biennale, the artworks in the jail will be removed, but what will be the lasting impact on the prisoners?