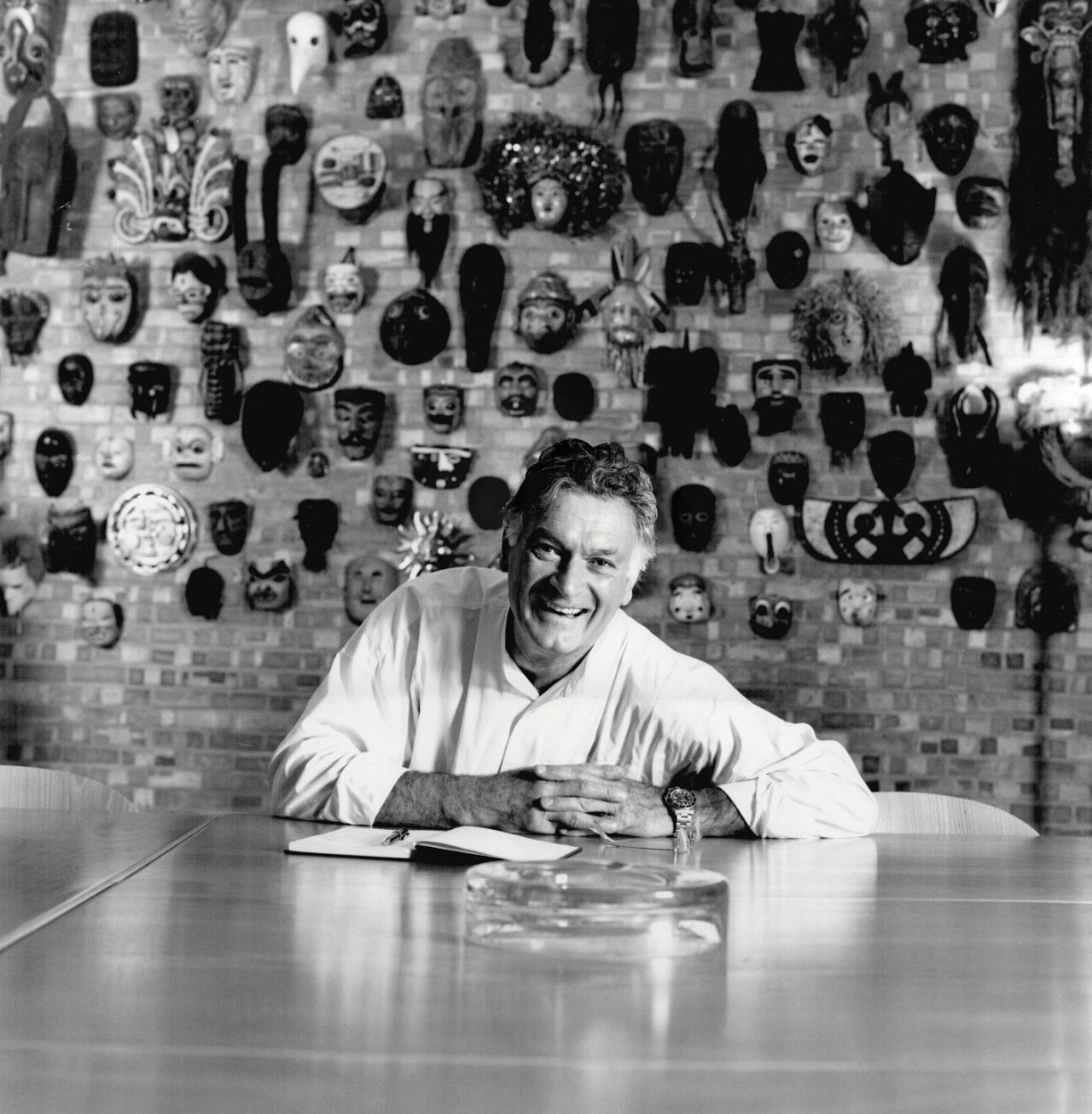

A tribute to Kenneth Grange, Britain's best kept secret industrial designer

British industrial designer Sir Kenneth Grange died this week aged 95. In tribute to his remarkable career and impact on our everyday lives, Euronews Culture lifts the lid on the leader of a revolution and the man Apple design guru Sir Jonathan Ive calls his hero.

A leading light of Britain's postwar industrial design went out this week as Sir Kenneth Grange died at the age of 95.

From pens to chairs to lamps via trains and taxis - Grange left his indelible mark across decades of design.

For some, he was the most influential industrial designer you’ve never heard of, although he was knighted for services to design and created some of the most iconic everyday products ever made.

Kenneth Grange was the very definition of a renaissance man. Over his 70-year career he designed hundreds of products for dozens of global brands. He was such a prolific designer of beautiful, functional, everyday objects, it’s likely you’ve used his products.

A new book was released in June about his extraordinary work and London’s Victoria and Albert Museum taking charge of his extraordinary archive, which gave Euronews Culture a unique chance to look back at the career of the man who introduced UK industrial design to the world and quietly inspired a generation.

From the Kodak Instamatic camera and Wilkinson Sword razors, to the Kenwood Chef and Parker pen, he even redesigned the iconic London taxi and Anglepoise lamp.

Whatever the project, the philosophy that made Grange the go-to designer from the 1970s onwards, shines through - economy of design, a rejection of flourishes or unnecessary adornments, the superfluous stripped away, form following function and the needs of the user always coming first - and finally, a dash of British wit.

Starting from scratch

Born in London 1929, Grange studied technical drawing before his undertaking National Service in the late 1940s. He emerged from the army to a Britain fizzing with energy and new ideas on how to build a better world from the rubble of the Second World War.

Back then Britain was taking its first stuttering steps in the new world of industrial design. The infrastructure to train designers didn’t exist. There were no courses, no designers to emulate – even the word ‘design’ was new to the national lexicon.

The consumer culture we take for granted today, with brands jostling to seduce with their good looks, was just emerging. Grange wanted design to play a role shaping this new world.

It was while working as an architecture studio apprentice in the late 40s, early 50s, that Grange got his first and most important break, he met architect Jack Howe.

Howe, a seasoned architect and creative who had a passion for industrial design, took Grange under his exacting wing. Over the years they worked together they defined and refined the notion of an industrial designer. Grange credits Howe with giving him his big break and teaching him the principles and practices that would define his work.

When Ken met Ken

In 1958 Grange went solo and set up Kenneth Grange Design. One of his early clients was Mr Ken Wood, of Kenwood kitchen appliances fame. Grange didn’t know then that their meeting would herald the start of a relationship that would become one of the most prolific and enduring of his career.

In Kenneth Grange: Making the Modern World, Grange recounts meeting Wood, soon after being given four days to develop a new design concept for the ageing Kenwood Chef food processor.

Realising he didn’t have time to complete the model of his design, Grange shaped half of the symmetrical model and added a mirror to complete the whole. Wood appreciated the innovative solution as ‘a creative sales technique’ and Grange believed “it was this problem-solving approach as much as the design itself” that made Wood decide to appoint him.

Grange’s redesigned Kenwood Chef launched in 1960 and sold millions of units, doubling previous sales figures. Its success marked the birth of a relationship that would transform the fortunes of both Kenwood and Grange.

Five guys named design

In 1972 Grange pushed the envelope again by becoming a founder of one of the country’s first multi-disciplinary design agencies, Pentagram. The calculation the five partners made was that as the design ecosystem grew, big clients would be more interested in dealing with other organisations, rather than with freelancers – they created an early design one-stop-shop.

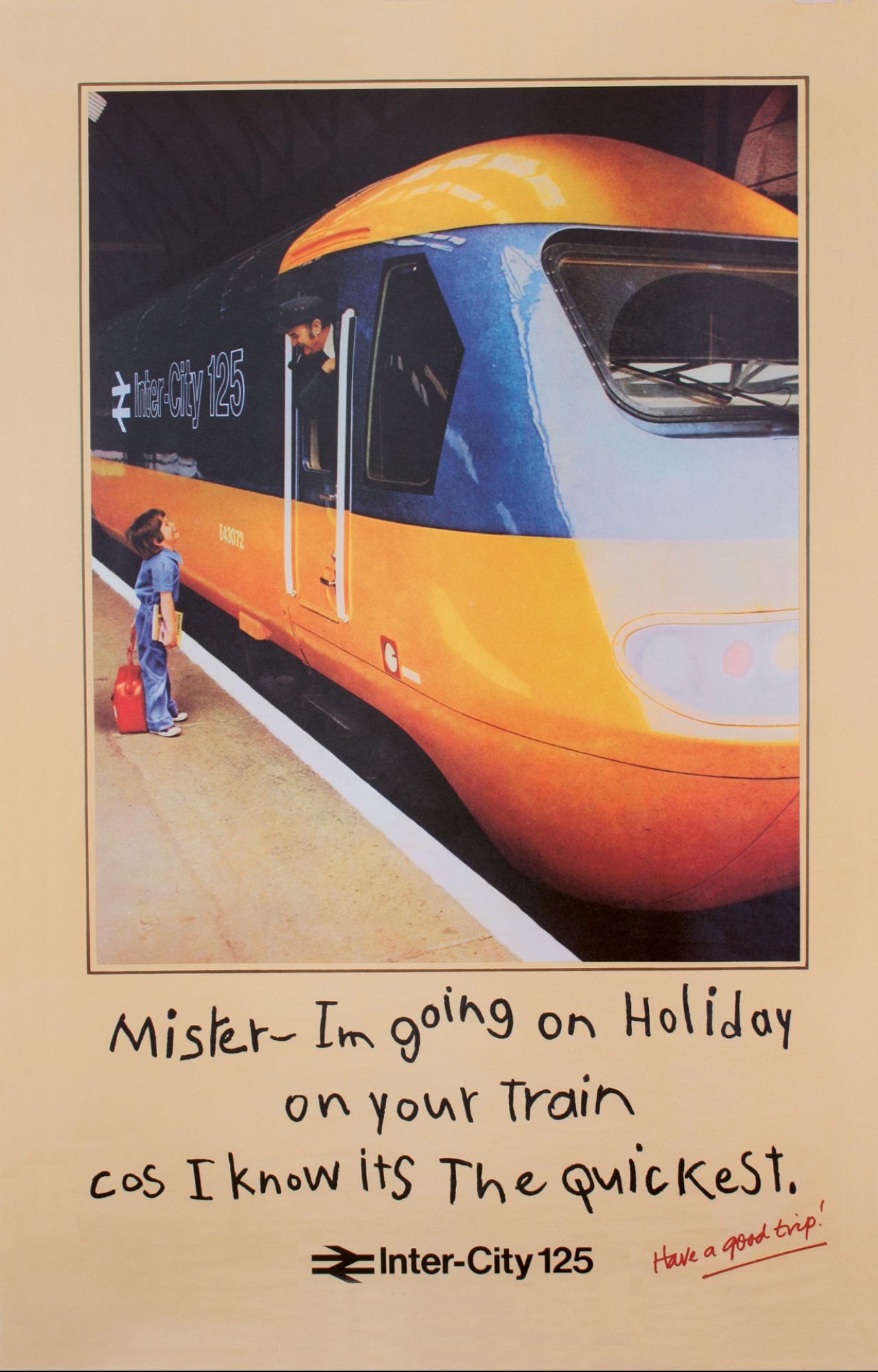

It was while at Pentagram that Grange secured the commission of his career, to design the look of the power car driving the InterCity125.

In Kenneth Grange: Designing the Modern World, author Lucy Johnston describes how although Grange was employed to perform an important, but not a central task, his desire to create a better product compelled him to do more.

Grange overstepped his brief and analysed the impact different shapes at the front of the train had on aerodynamics and performance - not an area of interest for British Rail at the time. His insights led to a design that was a sensation - it screamed, ‘this is the future’. Not only did his design look great, it also boosted the train’s performance was also boosted - a Grange prototype set a diesel world speed record of 230.5Km/h (143.2 mph).

The Inter-City 125 went into production in 1975 and retired in 2019. It became a design classic that elevated Grange and British industrial design to a new level.

Lucy Johnston told Euronews Culture her theory of why, despite Grange’s many successes, he is largely unknown outside of the design world:

“If Kenneth was doing his work today he would be more of a celebrity. In some fields for some of his work he is. The Inter-City 125 train has a global fanbase in the train loving community - they turn out in their droves to see the train and if Kenneth is attending, he gets mobbed.

“In some pockets he is famous, he’s a design celebrity, but not like a Jonny Ive today. He’s not globally known in that sense and wasn’t, just because of the nature of the industry at that time. He was one of the first - design didn’t have the same household awareness that it has now – but he liked it like that way.”

Jonathan Ive, who wrote the forward to the new book about Grange, named the Inter-City 125 as his favourite Grange design. He said: “I remember taking a day return from London to Bath solely to ride on his train. I love its complete rejection of arbitrary form, or space-age design aspirations without function.

“For his services to humility, for his love of making and his enormous impact on the visual culture, Sir Kenneth Grange is a hero of mine and of British design.”

With the release of Kenneth Grange: Designing the Modern World and the Victoria and Albert Museum making his archive available to future generations, the best kept secret in postwar British industrial design is out.

Kenneth Grange, industrial designer, 1929-2024.