Deep within an east London basement there exists a Clown Egg Register that trademarks clowns' looks. Euronews Culture writer Amber Bryce visits in search of an eggs-planation.

It’s 2pm on a gloomy Tuesday and I’m on my way to a clown’s basement to view a collection of painted eggs.

No, this is not the opening to a horror movie - just journalism in the name of International Clown Week (1-7 August), and definitely not my own selfish desire to see an eccentric pocket of London.

The clown I’m visiting is Mattie Faint, a professional performer for over 45 years and trustee of Clowns International, the oldest society for clowns and friends of clowns.

Its collection of costumes and props were once housed at the Holy Trinity Church in Dalston (also known as the Clown's Church) but had to be moved following a flood in 2018. Now they reside at Faint's Clerkenwell home.

I’m thankful he’s not wearing the clown outfit when I arrive. It’s not that I’m afraid of clowns - I love their colourful outfits, makeup and garish goofiness - but I am also haunted, like many, by a childhood of watching Tim Curry as Penywise in the 90s miniseries adaptation of Stephen King’s "IT".

When I briefly raise this fear with Faint, he seems a little insulted: “Clowns aren’t scary!”

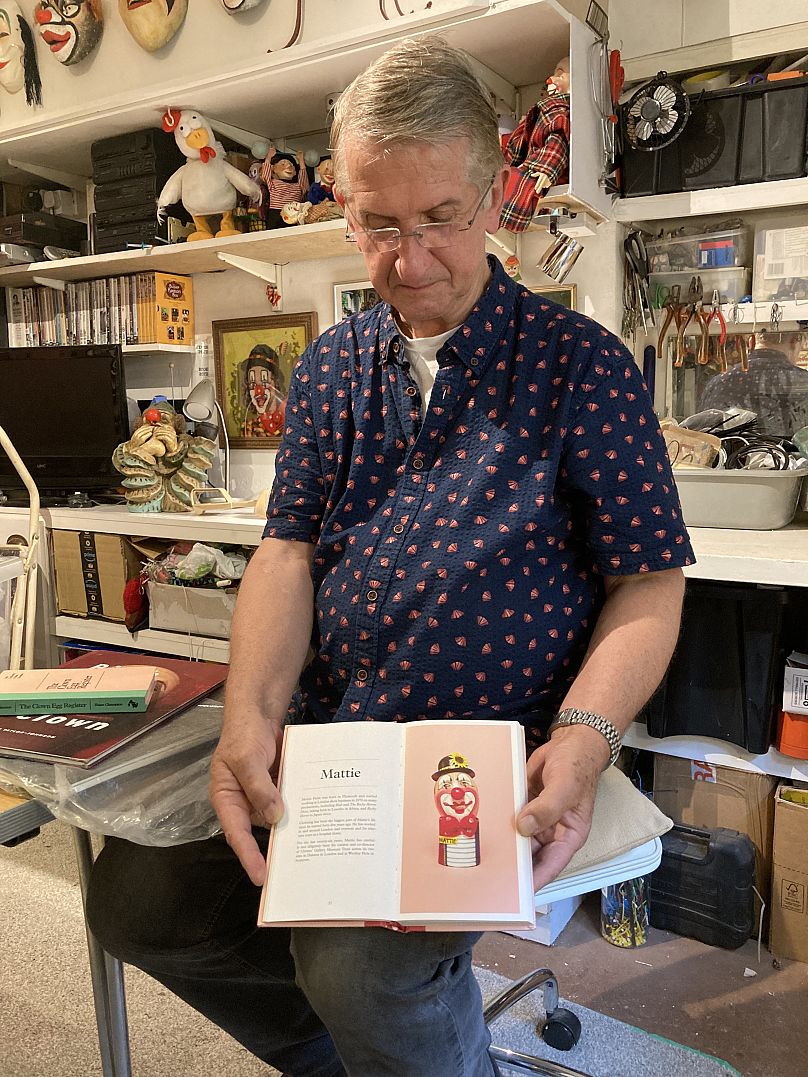

And so we go to his basement; a hallway adorned in vintage Harlequin paintings, a bicycle horn, very small violin, and ceramic jester heads leading us to a small room where the Clown Egg Register awaits.

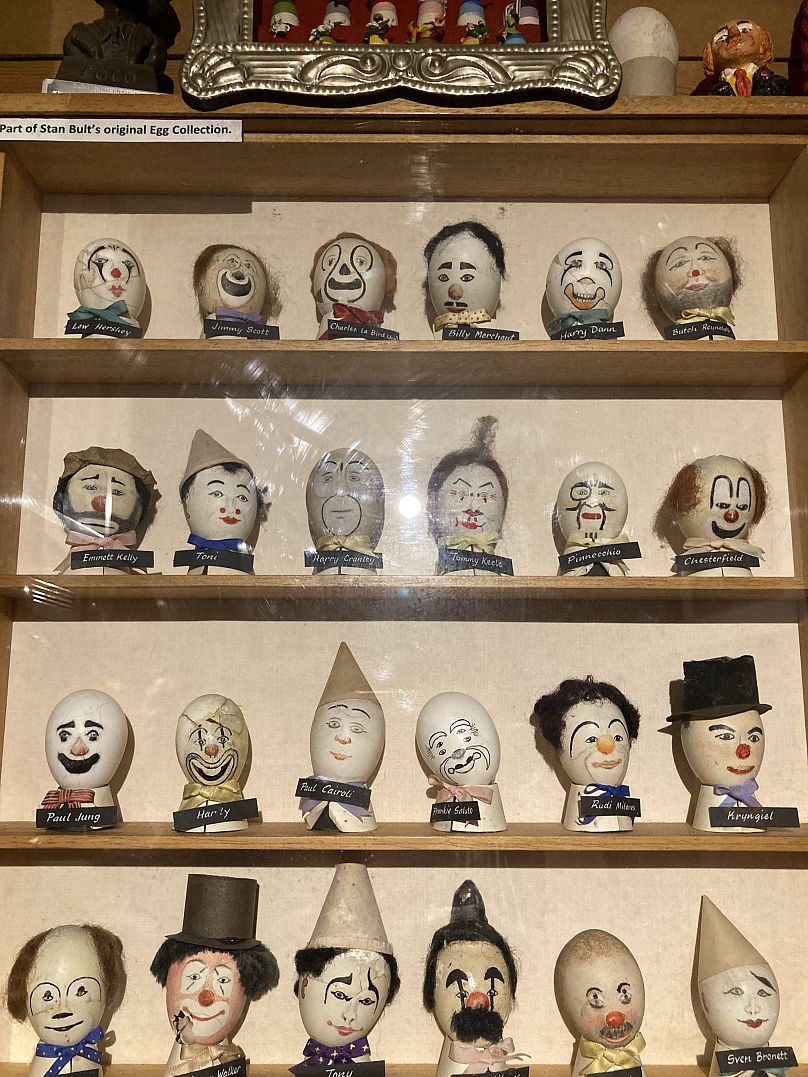

A collection of over 250 eggs painted with clowns’ faces, this is how clowns can officially record their looks and names - and the only registry of its kind to exist in the world.

“These are real impressions of the person who wore the face. Each one has its own little character,” Faint says, gleefully.

It all began in 1946 with Stan Bult, a Londoner who founded Clown’s International and started drawing the faces of its members on chicken eggs as a method of archiving them.

“Bult was never a clown. He set up the organisation because clowns used to meet around Grimaldi's grave after the war and he was there to take pictures,” Faint explains.

“He formed the first club with no internet, barely a telephone and everybody writing letters. All the clowns would meet in February before the season started to give thanks, because the circus is dangerous work. Most of these are painted from life.”

Bult painted 350 eggs in his lifetime, many of which sadly got broken or lost over the years.

“The old eggs were actually in a restaurant on Dover Street, just off Piccadilly. I went there in 1970 and remember it; all these eggs were in a showcase in the centre. The restaurant closed, but then this woman phoned us and said, 'My father's just died and we found this showcase in his spare bedroom, screwed to the wall, with all these eggs in it. Would you like to buy them for your collection?' So we bought them back.”

At this point, Clown’s International had already started a new register that included copies of the originals, painted on sturdier ceramic eggs.

To have one done, clowns must register with the society and pay £60 (€71) for two eggs, one of which is archived. Their looks and names are also evaluated by a small committee.

“One woman wanted to call herself Coco and we said, 'No! You can't be called Coco. Out of all the names to choose, Coco is a very famous clown.' So she changed the name to coconut. That was allowed.”

Looking at the eggs brings a great sense of joy, an array of smiling faces made all the more beguiling when bulbous. The stories behind each are a fascinating insight into the history of the clowning community, too.

There are the quadruple eyes and exaggerated smile lines of the late Frank Saluto, a famous 3 '10 American clown whose career lasted 46 years.

A face-engulfing grin and tuft of orange frizz sprouts from Jimmy Scott, a British auguste - the European name for a traditionally red-nosed and perpetually clumsy, comedic circus clown.

I also learn that Foottit and Chocolat were performers in the Paris circus in the 1900s, with Chocolat, whose real name was Rafael Padilla, one of the earliest successful Black entertainers in France.

“So this is my egg,” Faint says, holding up one with a big red nose, tiny sequinned bow tie and top hat pinned with a sunflower.

“I was quite quick about creating my look, actually. I focus a lot of my makeup on Coco's face,” he says - Coco being Nicolai Poliakoff, the best known UK clown of the mid-20th century.

“My eyes are very similar to Coco's, and my mouth is similar, but in red, with the line around it. So yeah, I drew inspiration, I think is the best term, from Coco. And who better to?”

Clowning around

While I'd come for the eggs, I stay for Mattie the Clown.

Sitting in what looks like a cross between a chaotic dressing room and a charity shop specialising in cirque du bric-à-brac, we chat for over two hours about his colourful life.

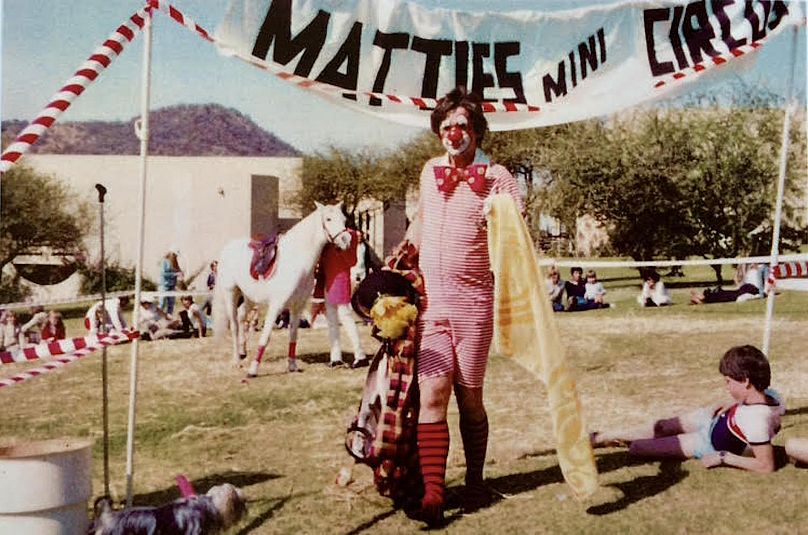

After moving to London, Faint began his career as a clown in 1971: “Mattie the Clown is just me. It's my other self. I don't think it's my alter ego. To put on the character you put on the persona. You become the clown.”

His very first ‘motley’ costume was stitched by Lindy Hemming, who would go on to design costumes for everything from Casino Royale to The Dark Knight to Wonka, winning an Academy Award in 1999 for her work onTopsy-Turvy.

Faint was always a natural performer, with a background in theatre that includes working on ‘Hair’ at the Shaftesbury Theatre and as a regional stage manager on ‘The Rocky Horror Picture Show’, which he also took to Africa and Japan twice.

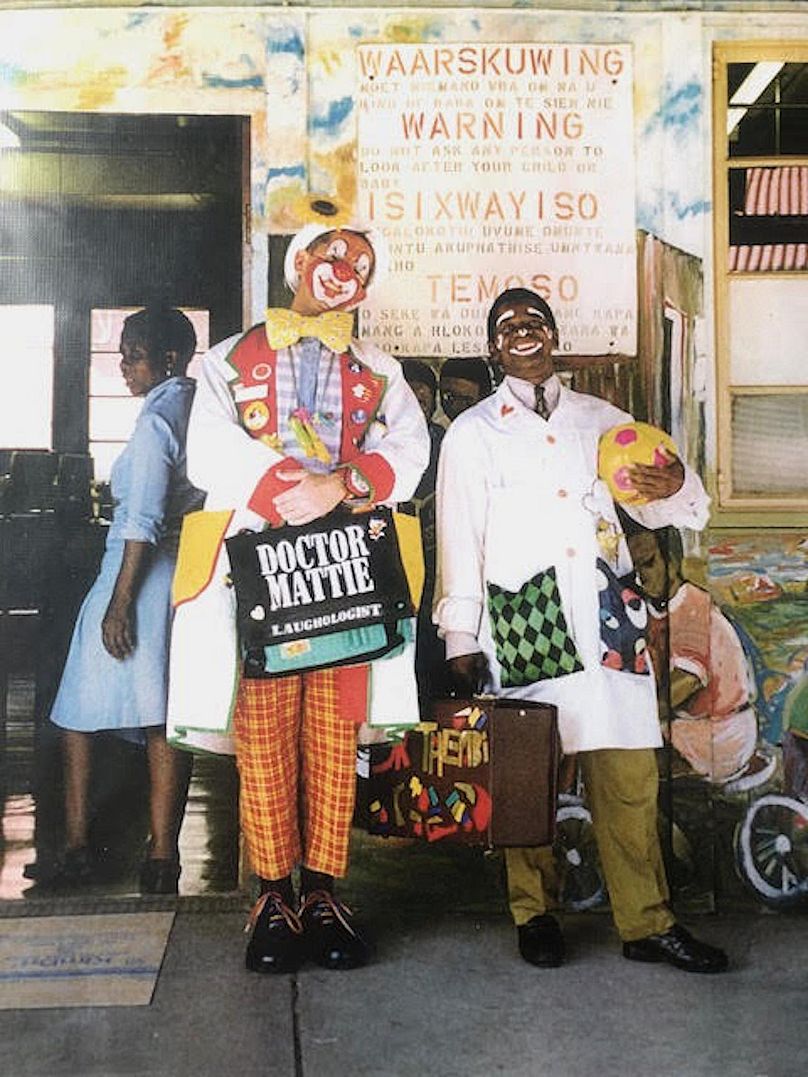

For 19 years, he worked as a ‘giggle doctor’ for the Theodora Foundation, an organisation that hires entertainers to help sick children in hospitals. While incredibly rewarding work, it wasn't always without its hiccups.

“When I first started at Great Ormond Street Hospital, I got the costume on for the first time and came out. There were two people standing there, like this [motions looking sad]. They looked at me and I went, 'Hello!' [silly clown voice] And they just went, 'Alright.' I said, 'Ooh, you don't look very happy!' And they said, 'No, we're not. Our son's just died.'"

They hugged afterwards and it was all ok, but the thought of dealing with such intense situations - and the emotional toll that must take - makes me think of the sad clown paradox, a theory that some comedy performers use humour to manage and make sense of a deep inner turmoil.

For Faint, performing has always been a way to escape the knotty existentialisms of being human for a little while.

“As soon as you're in costume, all that disappears, because you're working,” he explains. “Making people laugh, it's wonderful.”

Like watching a stream of bubbles bloom then burst, Faint's anecdotes are effervescent glimmers into not only another life, but another world. From meeting Queen Elizabeth II twice (and making her chuckle with a light-up red nose), to another about a clown friend that came out of retirement after decades only to have a heart attack on the train journey to work, they seamlessly fluctuate between comedy and tragedy.

While clowns can be scary in the alien-ness of their painted faces and aggrandised motions, their existence makes perfect sense in a world that can be even scarier.

They’re the embodiment of our need to laugh at the enforced seriousness of it all; of our desires to be someone outside of ourselves, even if that someone has a little squirty flower.

In playing the fool, there’s freedom.

“I once passed a mother who worked at the hospital and her son. I said to him, 'Hello!' [in a silly clown voice] and he said to his mum, 'Who's that mummy?' And she said, 'That's Mattie the Clown disguised as a man,'" Faint says, adding: “Do you know what? That's what I want written on my tombstone.”