Pollution neutralising clothing and a dress that dissolves in water. The unique creations of British designer Helen Storey have a new home at the London College of Fashion. Euronews Culture meets the quiet genius inspiring a generation of socially conscious designers.

Fashion designer and social artist Professor Helen Storey has a complicated relationship with the fashion industry. Despite being fashion royalty, she worked with Valentino in Rome and created her own award-winning label, she believes the industry can do more for humanity than create ‘more stuff’.

Her unique and sometimes provocative take on fashion has seen her designs question traditional notions of glamour, expense and women’s image. Over her 30-year career her collections have predicted societal trends, from the early 1990’s 2nd Life recycling range, creating boas from recycled rags, and evening gowns from plastic bin bags – laying the ground for the pre-loved clothes market.

Now her life’s work of more than 2,000 items, including hats, dresses, sketches, plans, film and conceptual ideas, have been donated to the University of the Arts London (UAL), so future generations can analyse how she redefined fashion’s purpose and created clothing with a conscience.

Rage against the machine

Storey’s journey to fashion immortality took her from Kingston Polytechnic, where she graduated in Fashion in 1981, to Rome to work with legendary Italian fashion houses Valentino and Lancetti. Back in the UK she briefly worked with British fashion firm Bellville Sassoon before taking the plunge and launching her own fashion label in 1983.

Free to experiment, her designs dialled up the levels of challenge and quiet provocation to eleven. Her 1990 collection titled 'Rage', railed against the notion that women were supposed to be ‘a nappy mother by morning, a shoulder-padded woman by day and a lover and sex goddess by night’.

'Rage' won her the British Fashion Council’s Most Innovative Designer of the Year award and a nomination for the coveted British Designer of the Year prize. Although she lost out to Dame Vivienne Westwood, the accolades brought global attention and established her as one of Britain’s most provocative talents.

After more than a decade in the commercial fashion world Storey closed her business to pursue a passion for cross-discipline collaboration and radical experimentation, producing jaw-dropping designs that brought science and art together to address the big questions of our time.

She told Euronews Culture that there was an inevitability about her move to the experimental side of fashion: ‘To run a fashion business you need to know what you’re going to do next, but I didn’t always know what that would be – I’d be experimenting with themes, materials, ideas which would take us into unpredictable design space.”

Primitive Streak

Those ideas spawned a series of beautifully challenging designs that combined science with art, design and politics. Her 1997 Primitive Streak collection was created to capture public imagination around an area of science in a unique and unexpected way, in this case the creation of life.

Working with her biologist sister Professor Kate Storey, the project charted the first thousand hours of human life. Eleven key stages of embryonic development were realised in fabric, print and stitch - fertilization, cell division, heart development, spine and rib formation, were realised through custom made textiles, embroidery, & fibre optics.

A double award-winning project, Primitive Streak has been seen by 5 million people across 10 countries.

Her 2008 project Wonderland explored innovative ways to use and dispose of plastic packaging, in response to the wasteful modern throw-away culture. Storey was intrigued by the idea of plastic bottles having a second life once empty, extending their usefulness and relevance.

With scientific collaborator Professor Tony Ryan OBE (Director of The Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures & Professor of Physical chemistry at the University of Sheffield), Storey created a dress from a polymer that breaks down when in contact with water, leaving a residue that can be used as an alternative growing medium for plants.

Ever the show woman, Storey unveiled the Disappearing dresses to the world with a theatrical flourish. A series of the dresses hung artfully above vast vats of water. As music played the dresses descend into the liquid over days. The polymer material dancing as it touched the water as the dress slowly dissolves - fashion as performance art and subtle political statement.

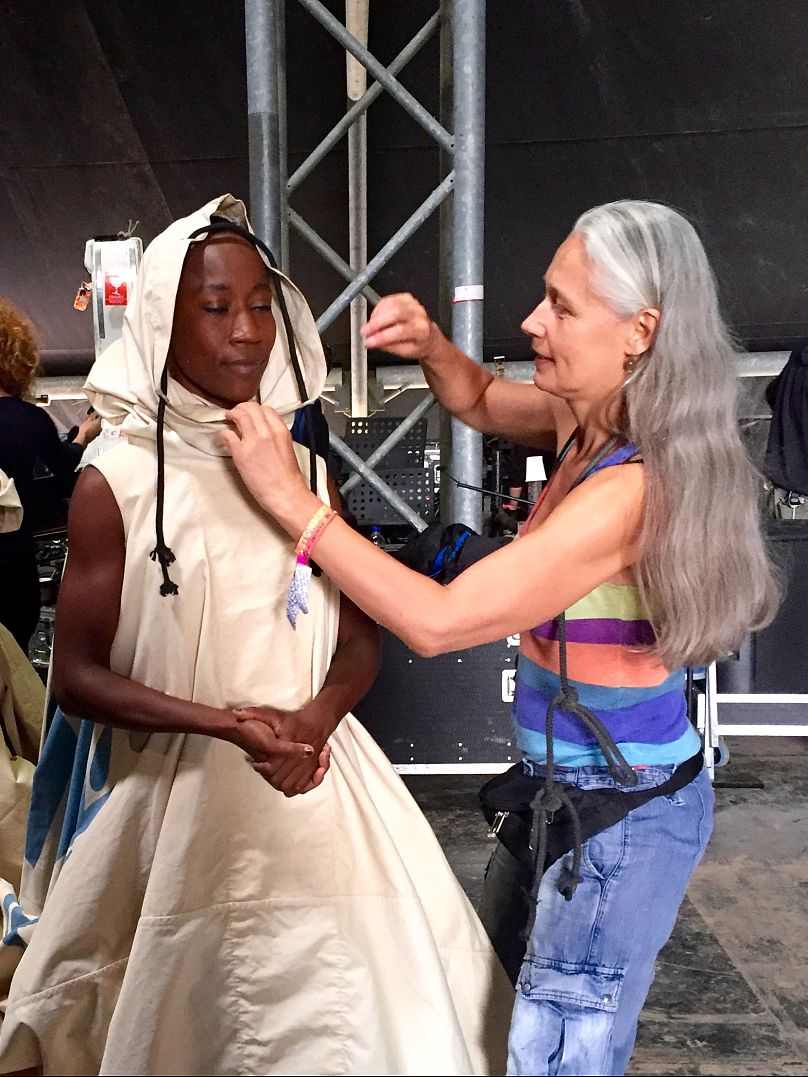

Standing in the London College of Fashion archive, Storey wears gloves as she shows Euronews Culture a rare surviving Disappearing dress. It is so delicate body heat could damage it. Although fragile in form, the issues and ideas the dress highlighted and its power to spark discussion about sustainability, pollution and consumerism, are still strong.

Catalytic Clothing

In 2011, Storey and Ryan created Catalytic Clothing, a ground-breaking project looking at how existing technology could be harnessed differently to improve air quality. A catalytic dress called ‘Herself’ was borne out of the collaboration.

The garment repurposed nanotechnology used in the building trade to create clothing capable of neutralising pollution from the air. Storey’s design was impregnated with a photocatalyst rich concrete, that uses light to breakdown air-borne pollutants, rendering them harmless – although using concrete ‘pearls’ was a quick fix, it proved that the concept worked and was later developed for denim and other fibres.

The ultimate aim of the project was to create a laundry additive that would give existing clothes pollution busting properties to the clothes you already own - the more people who wore photocatalyst boosted clothes, the greater the environmental impact.

Storey told Euronews Culture that although talks were held with manufacturers, a few challenges emerged, not least the fact that once washed, the garments would forever be pollution busting – so there would be no need to buy the product again. Great for air quality, not so great for the bottom line.

Storey accepts that failure, mess, powerlessness and humility are all part of the experimentation process. Taking risks combined with a willingness to be guided by the work - wherever it may take her characterises Storey’s approach to her art.

She hopes her archive inspires young designers to be brave and open as they embark on their own creative journeys.

Professor Helen Storey’s archive is housed at the London College of Fashion