From handwashing to protein analysis, here's how some world-changing innovations weren't always recognised immediately.

From the wheel to Wi-Fi, human progress has been defined by the brilliance of its ingenuity and the inventions we produce. Through awards and history books, we celebrate many of humanity’s greatest inventors.

While Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2022 for their work on the mRNA vaccines that were pivotal in turning the tide against the Covid-19 pandemic just a year prior, it can sometimes take a little bit longer for our brightest minds to get their due recognition.

Here are a few of history’s great inventors who we couldn’t live without today, even though their incredible work wasn’t immediately seen for its paradigm-shifting qualities.

Ada Lovelace

Augusta Ada Byron was the only legitimate child of the poet Lord Byron. She’s better known as Ada Lovelace after she married William King, from whom she gained the title Countess of Lovelace.

For those unaware, you may be surprised to find out that although she was born in London in 1815 and died in 1852, Lovelace is widely considered to be one of the pioneering intellectuals behind modern computing.

Despite her father’s literary proclivities, Lovelace was raised by her educational reformer mother Anne Isabella Milbanke, who ensured she had an appreciation for science and mathematics.

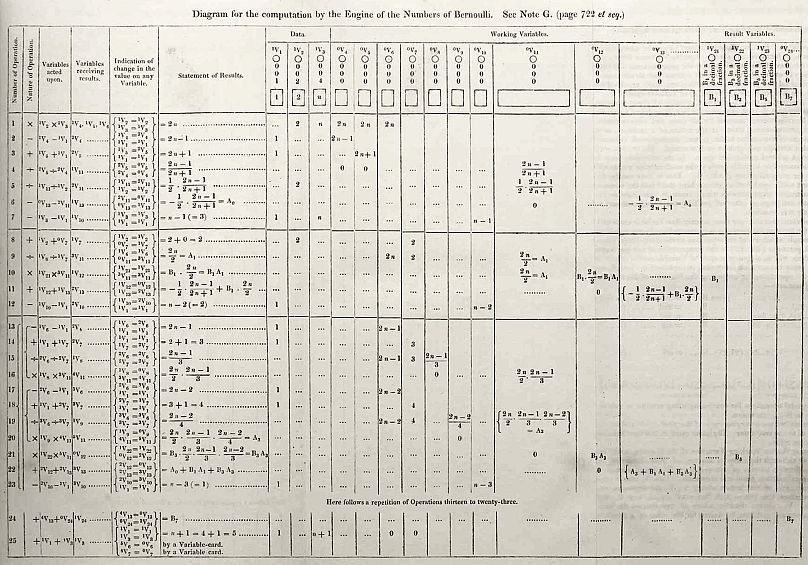

She worked alongside Charles Babbage, often considered the “father of the computer” on his research into the Analytical Engine, an automatic calculation machine that could compute complex arithmetic. Lovelace helped Babbage by translating an article by Luigi Menabrea and expanding on his work to create the Analytical Engine’s programming algorithms.

Sadly, Lovelace lived a sickly life and died before the Analytical Engine could become a physical reality. But her impact on computational programming languages remains to this day.

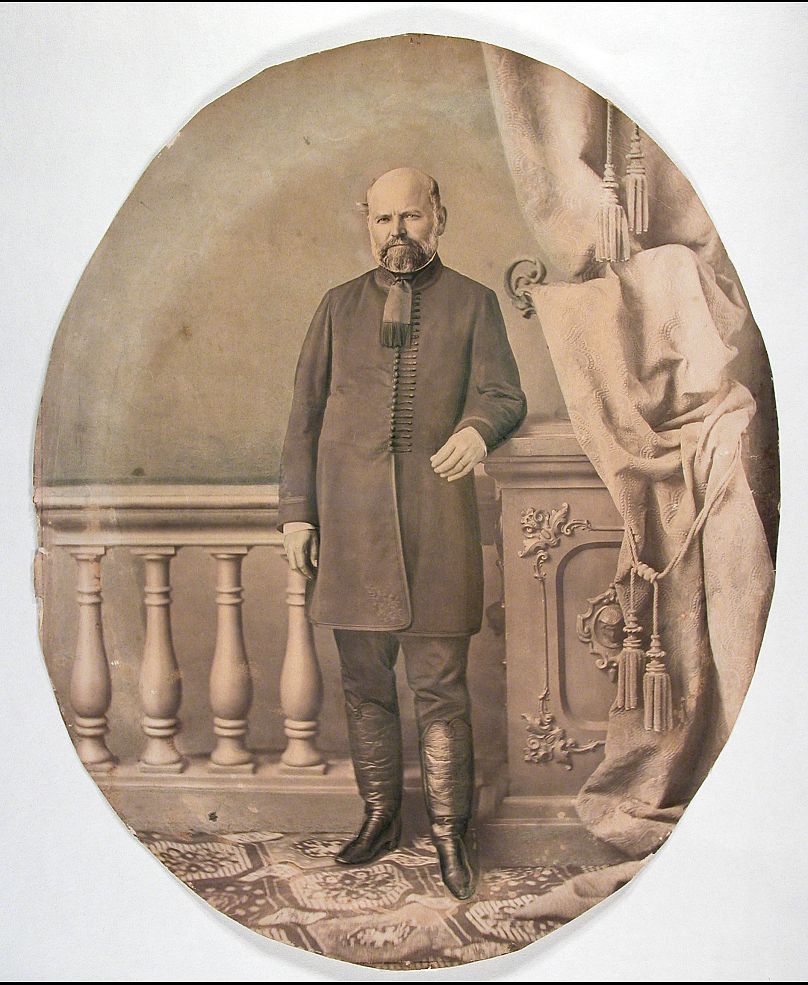

Ignaz Semmelweis

Sometimes, great ideas are overlooked when they’re first suggested. If only that’s all Ignaz Semmelweis had to deal with. Instead, he was shunned almost entirely by the scientific community. His crime? Suggesting that doctors should wash their hands.

In many ways, the Hungarian scientist’s discovery is a definitive example of how one person’s genius can change the course of humanity. Today, we take the health benefits of washing our hands for granted, but in Semmelweis’ time - in 1847 - it was revolutionary.

Semmelweis was a doctor in the First Obstetrical Clinic of the Vienna General Hospital. He observed that many of the women were dying of puerperal fever shortly after giving birth. Crucially, the mortality rate was five times as bad in the ward staffed by male doctors as in the midwives’ clinic, which was staffed by women.

He realised that because in the doctors’ ward, they performed autopsies on bodies, staff were accidentally passing “cadaverous” particles onto healthy patients. Semmelweis ordered his staff to start cleaning their hands and tools with chlorine. Amazingly, the mortality rate fell immediately.

Semmelweis’ discovery of the benefits of handwashing didn’t go down well. Some doctors believed he was accusing them of getting their patients sick. He was! It didn’t help his career though, and shortly after the ward stopped using chlorine and Semmelweis was fired. It may have taken some time, but Semmelweis’ discovery is now so commonplace and it’s impossible to measure the number of lives his simple suggestion may have saved.

Alice Ball

Born in 1892 in Seattle, Alice Ball was a top student and made history just by getting her master’s degree. When she graduated with her master’s in chemistry in 1915, she was the first woman and the first African American to do so at the University of Hawai’i. She then became the first African American research chemist and instructor at the institution.

Ball’s impressive academic record got her a job researching treatments for leprosy. At the time, leprosy was highly stigmatised and infected people were often sent to leper colonies to die. Despite lacking knowledge of potential treatments within Western medicine, traditional Indian medicine had a treatment in the form of oil from the chaulmoogra tree.

The problem was that this chaulmoogra oil was hard to apply topically and couldn’t be injected due to its thick viscous texture. Aged just 23, Ball developed the ingenious methodology of saponifying the oil – turning it into a soap – and creating chaulmoogra acid, which could then be combined with a liquid and injected.

Because the oil’s healing properties could now be put directly into the body, leprosy could be more effectively treated. Sadly, this all came shortly before her own death in 1916, at age 24. Ball never published her findings and her study advisor Arthur Dean put his name to her discovery, coining “the Dean method”.

Today, Ball is recognised for her achievement. Her contribution was first mentioned in a journal article in 1922, renaming the technique as “the Ball method” and the University of Hawai’i dedicated a plaque to her in 2000 beside a chaulmoogra tree.

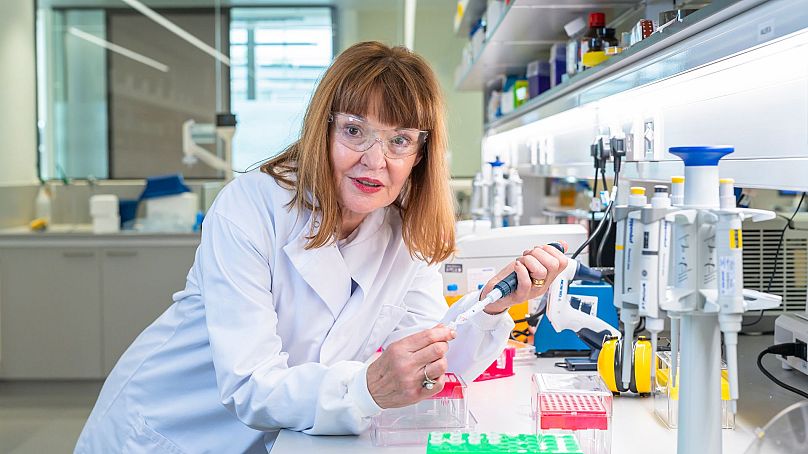

Dame Carol Robinson

Jumping forward to the 21st century, Dame Carol Robinson also made history at two of Britain’s top institutions when she became the first female chemistry professor at the University of Oxford in 2001 and the University of Cambridge in 2009.

Upon beginning her research in mass spectrometry – the analytical tool to detect the makeup of molecules – it was generally believed that proteins couldn’t be studied in their gas phases as they wouldn’t retain their structure.

Robinson persevered and developed her technique of “native mass spectrometry”, which preserves proteins in their natural state to be analysed. Thanks to this breakthrough, the complex structures of proteins can be studied, which has been immeasurably beneficial to the pharmaceutical industry, advancing not only drug discovery but also personalised medicine.

Robinson was a pioneer in other ways too, as the first female Professor of Chemistry at both Oxford and Cambridge Universities, Robinson was appointed Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 2013 and will receive the Lifetime Achievement award during the European Inventor Award 2024 ceremony on 9 July in Malta. The award is hosted by the European Patent Office (EPO), and you can watch it live on euronews.com at 12h CET. The award is hosted by the European Patent Office (EPO), which will be live streamed here.