Amid the war in Ukraine, which is increasingly being waged in cyberspace, countries need to clamp down on malicious technological actions, rather than the weapons used themselves, Helene Pleil writes.

Cyberspace, encompassing the internet and other connected digital technologies, offers tremendous benefits but also poses significant risks as a military domain. This necessitates the existence of increased cybersecurity and cyber diplomacy.

The discussion and regulation of the militarisation of cyberspace have gained relevance due to greater uses in modern conflicts. The war in Ukraine is an example of an open military conflict also occurring in cyberspace.

Historically, arms control has been vital in preventing military escalation. Yet, creating applicable and verifiable measures for cyber arms control is challenging due to the unique nature of cyberspace.

A recent analysis conducted with colleagues from Technical University Darmstadt highlights several key obstacles:

What is a ‘cyberweapon’?

A fundamental challenge for establishing arms control in cyberspace is the lack of clear, uniform definitions of key terms. This is especially relevant since the conventional definition of a weapon does not truly relate to the characteristic of a cyberattack used as a “cyberweapon”.

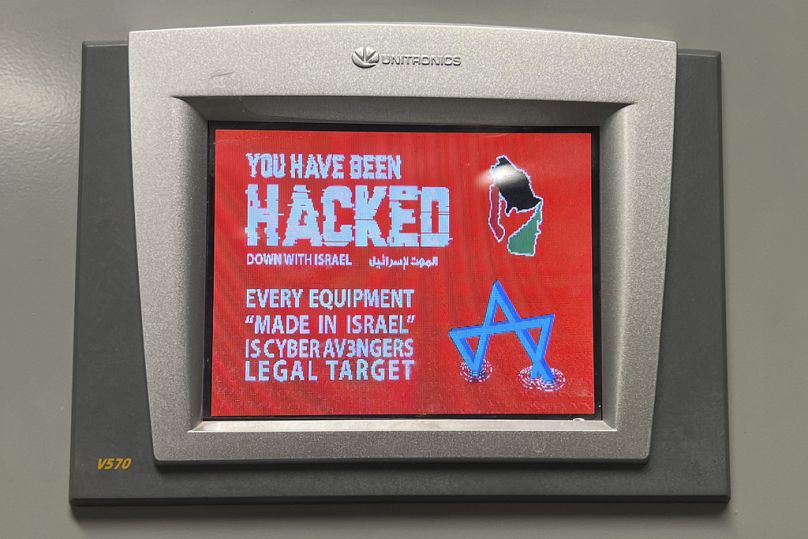

Cyberweapons tend to be data and knowledge that are capable of being conceived and executed to compromise the integrity, availability, or confidentiality of an IT system without the owner's consent.

Thus, some experts we spoke with debated that the concept of a cyberweapon itself does not exist since a weapon suggests some sort of kinetic, physical use. Cyberattacks exploit vulnerabilities in technology and can lead to real-world physical problems, but does that mean the trigger was a cyber ‘weapon’?

This ambiguity makes it difficult to establish what would be controlled under a cyber arms treaty.

Many everyday technologies, like computers and USB sticks, have both civilian and military applications.

No definitive line can be drawn between these different use scenarios; therefore, the products cannot be banned in fundamental terms for arms control. You can ban landmines or nuclear weapons, but you cannot ban USB sticks or computers.

Moreover, many instruments that can be used as cyberweapons are also instruments for building cyber defence or espionage.

While dual-use has played a role in arms control treaties in the past, the dual-use nature of cyberweapons takes on a completely different dimension than it did previously.

Verification for weapons control one of the biggest hurdles

Finding suitable verification mechanisms to establish arms control in cyberspace is extremely difficult. For example, for cyberweapons, it is not possible to quantify them. And we cannot count the weapons or ban an entire category, as has been the case with arms control agreements for traditional weapons.

Furthermore, without cost, cyberweapons can be infinitely replicated and shared around the world. For example, considering code, just deleting it from a device does not mean it is really gone; it could have ended up on a backup system or elsewhere on the internet.

This exacerbates the challenges of establishing suitable verification mechanisms as they would have to be extremely intrusive. Many states could be unwilling to participate in an intrusive verification process as they would have to provide insights into their own cyber defences, with the potential for these insights to be misused to spy on their vulnerabilities.

Cyberattack tools and technology evolve rapidly, often outpacing regulatory efforts. By the time a regulation is agreed upon, the technology may have advanced beyond its scope. This rapid evolution complicates any regulation or verification measures based on the technical features of software.

For example, the code of a cyberattack is usually based on ongoing software developments that are adapted for specific targets and tasks.

This means the code will change and evolve incredibly quickly. Variation will be extremely high, and future cyberattacks will always be different from past attacks.

Also, due to the dual-use factor and the fact that most cyberspace infrastructure is owned privately, the private sector would need to be involved and committed for arms control to be effective.

We need to go after harmful acts themselves

Political will is crucial for establishing arms control measures. States, recognising the strategic value of cyber tools by building up their capabilities in this domain, may be reluctant to comply with new treaties that limit their potential advantages. The current geopolitical climate further complicates efforts to gain widespread agreement.

From looking at the literature and speaking with experts, traditional measures of arms control cannot be simply applied to cyberweapons. Instead, the focus should be on banning certain malicious actions. This approach allows for agreements that can adapt to technological advancements and the dual-use nature of cyber tools.

Since 2015, international negotiations within the United Nations (UN) have led to the establishment of 11 norms for responsible state behaviour in cyberspace, aiming to limit state actions and define positive obligations.

However, these norms are voluntary and non-binding, leading to frequent violations. The challenge is to make these norms more binding and hold states accountable for malicious actions.

Attribution, the process of (publicly) assigning cyber operations to specific actors based on evidence, is a crucial tool in this regard. Once considered too complex, attribution is now increasingly feasible and could serve as a foundation for sanctioning the use of cyberweapons rather than the weapons themselves.

This should therefore be taken as a starting point for finding creative alternatives and solutions to arms control in the traditional sense. Thus, considerations in the direction of an international mechanism or institutionalisation of such processes are proving to be interesting.

Helene Pleil is a Research Associate at the Digital Society Institute (DSI) at ESMT Berlin.

At Euronews, we believe all views matter. Contact us at view@euronews.com to send pitches or submissions and be part of the conversation.